Civil War Diplomacy

Kinley Brauer

The importance of diplomacy during the American Civil War has long been underestimated. Both Northerners, who were committed to the preservation of the Union, and Southerners, determined to create a new nation, understood that without support from Europe, the secession movement in the United States was doomed. Thus, the foreign policy of the Union, in the able hands of Secretary of State William Henry Seward, was directed toward preventing the Confederacy from securing diplomatic recognition, military supplies, and any kind of encouragement from abroad. Toward that end, Seward conducted a vigorous foreign policy composed of bluff, bluster, and ultimately cautious moderation. The Confederates, on the other hand, were confident that the reliance of Britain and other industrialized nations of Europe on Southern cotton for their economic health and well-being and their desire for free trade guaranteed full support. Confederate foreign policy, therefore, was largely passive and dependent on King Cotton. Britain and France were indeed dependent on Southern cotton, and their leaders were convinced that the United States was irrevocably divided. All that was needed, they thought, was for the Union to recognize that fact. That conviction, a broad hostility toward slavery, an ample supply of cotton already in British warehouses, and a highly profitable wartime trade with the Union led to a uniform European policy of neutrality. That policy, however, which helped the North but hurt the South, was never carved in stone. Union blunders, British impatience, the actual and feared depletion of cotton stocks, and European horror at the bloodshed and destruction in America all threatened to move Europe from neutrality to intervention and Confederate success. Diplomacy, as much as military leadership, strategy and tactics, and Northern economic dominance, provided an essential key to the ultimate triumph of the Union and preservation of the United States as a single nation.

Because of the phenomenal development of the American economy and the expansion of the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, Europe and Latin America closely watched the American crisis unfold. The health of the economies of Britain and France depended greatly upon the import of American raw materials, primarily cotton, and access to the prosperous American market. Early on it was recognized that peace in North America best served European interests and therefore European leaders hoped that Americans would not engage in hostilities. They were convinced that restoration of the Union was impossible. When hostilities began, they decided that neutrality best served their interests.

The Confederate States of America also hoped for a peaceful separation. Shortly after his appointment as provisional president, Jefferson Davis and his secretary of state, Robert Toombs of Georgia, dispatched a mission to Washington to secure recognition and the transfer of all federal property to Confederate authorities. Davis and Toombs also dispatched three commissioners to Europe to explain the reasons for the creation of the Confederacy and to secure recognition and treaties of amity and commerce. Support from Europe, Southerners understood, was critical, for without a navy or industry of its own, the Confederacy had to have foreign backing. They placed primary reliance on European, and particularly British, dependence on their cotton, believing this ensured a favorable response.

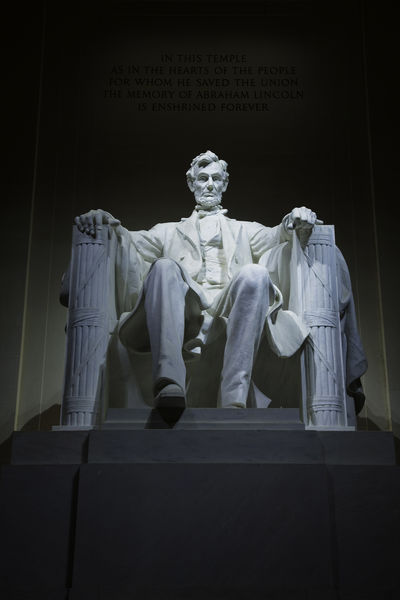

Northern leaders, particularly Abraham Lincoln and Seward, were absolutely committed to the preservation of the Union and also understood that the European reaction to the American crisis was critical. Seward, especially, believed that secession lacked majority support in the South and that Southern Unionists would rise and end the secession movement by the spring of 1861. It was essential that the Southern extremists receive no encouragement from abroad, without which expectation, Seward believed, the Confederacy would be short-lived.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Ephraim D. Great Britain and the American Civil War. 2 vols. New York, 1925. The classic study.

Bernath, Stuart L. Squall Across the Atlantic: American Civil War Prize Cases and Diplomacy. Berkeley, Calif., 1970. A superb analysis.

Blackburn, George M. French Newspaper Opinion on the American Civil War. Westport, Conn., 1997.

Blackett, R. J. M. Divided Hearts: Britain and the American Civil War. Baton Rouge, La., 2001. A thorough and sophisticated analysis.

Blumenthal, Henry. "Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities." Journal of Southern History 32 (1966): 151–171. An important essay.

Brauer, Kinley. "Gabriel Garcia y Tassara and the American Civil War: A Spanish Perspective." Civil War History 21 (1975): 5–27.

——. "The Slavery Problem in the Diplomacy of the American Civil War." Pacific Historical Review 46 (1977): 439–469.

Carroll, Daniel B. Henry Mercier and the American Civil War. Princeton, N.J., 1971. An excellent examination of the diplomacy of the French minister to the United States.

Case, Lynn Marshall, and Warren F. Spencer. The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy. Philadelphia, 1970. A thorough and judicious examination.

Clapp, Margaret. Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow. Boston, 1947. A biography of the American consul in Paris.

Cortada, James W. "Spain and the American Civil War Relations at Mid-Century, 1855–1868." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 70, no. 4 (1980).

Crook, D. P. The North, The South, and the Powers, 1861–1865. New York, 1974. An able synthesis that emphasizes British and Canadian relations with the Union and Confederacy.

Cullop, Charles P. Confederate Propaganda in Europe, 1861–1865. Coral Gables, Fla., 1969.

Duberman, Martin B. Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1866. New York, 1961. Excellent biography of the U.S. Minister to Great Britain.

Ellison, Mary. Support for Secession: Lancashire and the American Civil War. Chicago, 1972. Excellent study of the effects of the cotton famine on British opinion in the Lancashire cotton district.

Evans, Eli N. Judah P. Benjamin: The Jewish Confederate. New York, 1988. Especially strong on Benjamin's relations with Jefferson Davis.

Ferris, Norman B. "Diplomacy." In Allan Nevins et al., eds. Civil War Books: A Critical Bibliography. Vol. 1. Baton Rouge, La., 1967. An excellent starting point for books published before 1967.

——. Desperate Diplomacy: William H. Seward's Foreign Policy, 1861. Knoxville, Tenn., 1976. A study of the difficult first year of the war.

——. The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis. Knoxville, Tenn., 1977. Best detailed study of the crisis.

Hanna, Alfred J., and Kathryn Abbey Hanna. Napoleon III and Mexico: American Triumph over Monarchy. Chapel Hill, N.C., 1971.

Hyman, Harold, ed. Heard Round the World: The Impact Abroad of the Civil War. New York, 1968. Looks at the influence of the Civil War primarily on Europe.

Jenkins, Brian A. Britain and the War for the Union. 2 vols. Montreal, 1974, 1980. More recent and useful treatment than the Adams work.

Jones, Howard. Union in Peril: The Crisis over British Intervention in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, N.C., 1992. Excellent study of the mediation crisis of 1862.

——. Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. Lincoln, Nebr., 1999.

Mahoney, Harry T., and Marjorie Locke Mahoney. Mexico and the Confederacy, 1860–1867. San Francisco, 1998. Good narrative survey.

May, Robert E., ed. The Union, the Confederacy, and the Atlantic Rim. West Lafayette, Ind., 1995. Information on the impact of the Civil War on Europe, European colonies, and Latin America and examines the role of African Americans in influencing British opinion.

Meade, Robert D. Judah P. Benjamin, Confederate Statesman. New York, 1943. A good treatment of Benjamin's diplomacy.

Merli, Frank. Great Britain and the Confederate Navy, 1861–1965. Bloomington, Ind., 1970. Best study of the subject.

Monaghan, Jay. Diplomat in Carpet Slippers: Abraham Lincoln Deals with Foreign Affairs. New York, 1945. A popular study that overemphasizes Lincoln's role and is oversimplified.

Owsley, Frank L. King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America. 2d ed. Chicago, 1959. A full examination of Confederate diplomacy but somewhat dated.

Richardson, H. Edward. Cassius Marcellus Clay: Firebrand of Freedom. Lexington, Ky., 1976. Covers Union diplomacy with Russia.

Saul, Norman E. Distant Friends: The United States and Russia, 1763–1867. Lawrence, Kans., 1991. Based on research in both Russian and American materials.

Schoonover, Thomas D. Dollars over Dominion: The Triumph of Liberalism in Mexican–United States Relations, 1861–1867. Baton Rouge, 1978.

Smiley, David L. Lion of Whitehall: The Life of Cassius M. Clay. Madison, Wis., 1962. On Union diplomacy with Russia.

Spencer, Warren F. The Confederate Navy in Europe. University, Ala., 1983. Deals with Bulloch and Confederate naval warfare.

Stern, Philip Van Doren. When the Guns Roared: World Aspects of the American Civil War. Garden City, N.Y., 1965. A popular study.

Taylor, John M. William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand. New York, 1991. A readable popular account.

Tyler, Ronnie C. Santiago Vidaurri and the Southern Confederacy. Austin, Tex., 1973. On Mexican-American relations.

Van Deusen, Glyndon G. William Henry Seward. New York, 1967. A scholarly biography.

Warren, Gordon H. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas. Boston, 1981. A study of the first year of the war.

Willson, Beckles. John Slidell and the Confederates in Paris, 1862–1865. New York, 1932.

Winks, Robin. Canada and the United States: The Civil War Years. Baltimore, 1960. An able treatment of Canadian-American relations.

Woldman, Albert A. Lincoln and the Russians. Cleveland, Ohio, 1952. A narrative based on diplomatic correspondence from the United States.

See also Ambassadors, Executive Agents, and Special Representatives ; Blockades ; Embargoes and Sanctions ; Realism and Idealism .

And then he took out a firetruck toy and tried to kill me with it, but I was saved with my Krav-Magah techniques and lightning reflexes/instincts.

BAM.